THE DREADED BAG ZIP: FROM PERFUNCTORY TRANSFER TO TRANSFORMATIVE EXPERIENCE

The funeral consumers I meet aren't excessively distressed by today's funerals costs. More frequently, they are infuriated by the insensitive way funeral firm personnel, in the presence of family, transfer the dead to the funeral home from the beds they died in. "Then these two men in dark suits walked in, suggested we might want to leave the room, and we heard the zipping of a bag. Then they left. It felt like they were in a hurry to get to an appointment, or something." You yourself have heard this complaint. Funeral home transfer teams can bow and offer condolences until they're blue in the face, but if they can't manage a compassionate, careful collection of a deceased person from the room they just died in with grieving family members looking on, they have botched the funeral, and the funeral home's owner might spend the next three days trying to redeem the whole firm.

It is hard for such a loaded exchange to look as good or seem as smooth as anyone might desire. But the honesty and transparency of the moment is critical. Detaching medical equipment from the body, quickly reaching to support limbs that might hang down and look a little frightening in order to get the deceased person onto the funeral home's stretcher--all of those moments in the presence of family can be painfully awkward for the funeral home's hard-working (sometimes up-all-night) trade service or transfer team. In essence, this is a changing of the guard. It's not easy.

But I think success stems from engaging families more in the moment instead of fearing their reactions and trying to shield family members from the transfer's inevitable imperfections. The relocation of the dead from place of death to the next stop on the journey truly holds the most amazing, ceremonial potential! Some transfer teams see this moment of the funeral as the "worst" part when in fact, they could see it as the best and take greater pride in it. (Dare I say that many of the families wishing to pay less for a casket, would pay more for an improved transfer-from-place-of-death experience?)

We need to adapt to modern families wishing to witness as much as they can, even when what those families are choosing to see is difficult. It is not our job to remove them from an experience in order to "protect" them from it. Let's face it, the popularity of cremations without any funeral parlor visitation combined with the success of the hospice movement and home funeral have created an environment where the time spent at place of death is the viewing.

At this modern on-the-spot ceremony, family members may have been singing, praying, crying and just exchanging stories at the bedside in the 90-minutes since death occurred. The tributes have commenced before the funeral firm's arrival! Hospice workers, hospital chaplains, and death midwives are facilitating this new kind of working "wake" immediately after death exquisitely well. And families are navigating the liminal space--the time between death and disposition-- as best they can.

Enter the funeral director (or the funeral home's representatives). Yow. Not an easy moment.

Addressing my brethren directly, I'd like to demonstrate how funeral directors and funeral home personnel can support, even uplift, a grieving family at point of transfer.

1. Clear your head and fill it with compassion on your way to the home, hospice or hospital. Arrive at the agreed-upon time. Stand at the door of the room where the death has occurred, knock softly, then enter. Slowly offer your hand to family members, extend condolences. You've been doing that with every job, right? What's new is what comes next.

2. Ask what the people in the room called the deceased, and if you may use that name for a moment. Walk to the bed, touch the deceased's shoulder, and introduce yourself to the deceased by name and say you are there to help. This is a leap, I know. But hang in there with me. What is said next is open to personal style and cause of death. Among the possibilities: a moment of silence staring into the face of the deceased (telegraphing nothing but a calm, confident demeanor in death's presence). A very brief prayer could follow if the family is religious and no clergy is present ("God full of mercy who dwells on high, grant perfect rest on the wings of your divine presence..."). Or you could reflect out loud upon the fact that death is "a labor," and that the deceased has successfully gotten to that labor's other side. Death is not a lost battle.

3. Turn to next-of-kin and ask if everyone has said their goodbyes for now. (You must be willing to spend more time here if family members have still not completely collected themselves. You may have arrived too quickly, so be prepared to back off. Chances are good that they are ready, but you have no good reason to rush them if they're not.) Check, of course, for wedding rings and personal belonging. Remove if necessary, and offer to the next-of-kin. (There are legal papers to sign that declare that person the custodian of the those belongings now that may need to be signed.)

4. Again (now, this is key)--address the deceased by name and then say, "Forgive us in the coming minutes if we seem in any way awkward or clumsy as we take you to _________________. We are doing our level best, and we promise to continue to do our best as long as we, and the others we work with, are taking care of you."

I have found that even the most secular families appreciate this. Soul or no soul. People care that you care and that you are announcing your caring intentions. Did you notice how the family just took a huge sigh of relief?

5. At this point, turn to the family, and say, "Listen, it's fine at this point if you guys stay in the room, but you need to make a little path for our stretcher here. Or-- it's up to you--you might want to wait outside in the hallway." If you're a bit inexperienced and worried about being graceful with the body, your dream may come true: the family may tearfully retreat to the hallway and let you and your partner do the lifting in private. I feel grateful when I work for a family that wants to stay in the room. And, if I've got a do-it-yourself crowd, I might allow some family help at the feet, in the lift to the rolling cot, at this point. They may not want to do that much, in the tight space allowed, save tuck the sheet under. Or they may want to do a great deal. Either way, the offer to work collaboratively is what counts.

6. Now it's almost time to zip, but don't zip yet. Tell the family, "I'm going to cover and close but before I do, is there any music you would like to put on?" Any smart phone in the room on speaker creates this splendid opportunity. Any flowers on the bedside table? Ask the family if they'd wish to have the deceased exit with flowers in hand. Gently tug stems out of the vase, and tuck them in.

7. Now. Here is how to zip. Start slowly zipping at the feet. Continue to zip at an excruciatingly slow pace. This is just like a witnessed casket close. Stay formal. Be elegant. Go slow. Remember the compassion you brought through the door? Use it now most of all.

8. Stop your zipping at the base of the neck, with face of the deceased still exposed. Look up, and lock your eyes on the faces of the family members, indicating non-verbally: "Is it is okay to zip over the face?" Give them a moment to gaze at their loved one's face one last time. Wait for the nod. If you're not getting the nod, wait some more. The family eventually will nod when ready. And you've been helpful in preparing them for the road ahead.

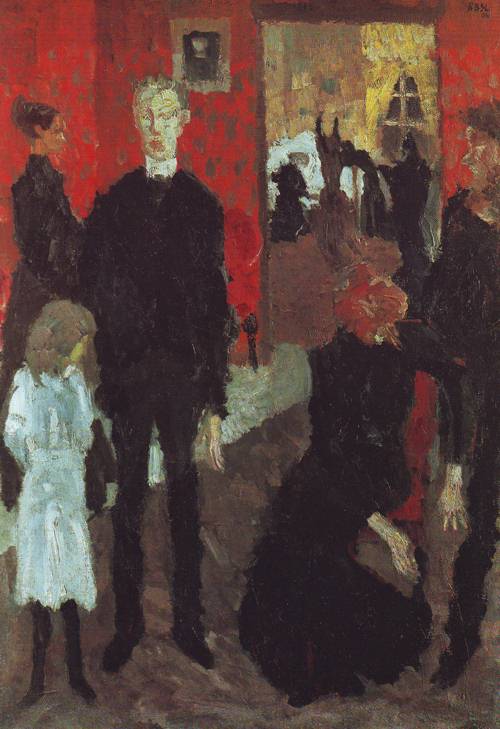

Cot cover from FinalEmbrace.com

9. I take my leave with this cot cover on top of the stretcher, gliding to music, as we roll down the hall. When the death has occurred in a residence, the exit may be even more effusive and elaborate. A parting poem? Solo sung by a family member? Absolutely. Even more terrific things can occur when the whole funeral was held in the home and you are now on your way straight to the crematory or cemetery. Louder music, rose petals cast as you graciously depart. Children or pets present? Get them involved too. This is it. This is now. No one will ever be quite the same again.

Thanks to Char Barrett, Jerrigrace Lyons, and Olivia Bareham whose trainings have strengthened my resolve to be a family-focused funeral director. Grateful thanks also to Kateyanne Unullisi, the celebrant and genius behind The Emerge Foundation, for her thoughtful notes on an earlier draft of this article.

Amy Cunningham is a New York City funeral director who serves Manhattan, Brooklyn Heights, Park Slope, Cobble Hill, Windsor Terrace, Ditmas Park families, helping them create distinctive funerals and memorial services. She specializes in green burials in cemeteries certified by the Green Burial Council, simple burials within the NYC- Metropolitan area, home funerals, and cremation services at Green-Wood Cemetery's gorgeous crematory chapels.